“You build it, you run it” is a fine principle, but it means you need to let your teams make their own choices. No one wants to support a system running on [insert inappropriate or flaky technology here] just because that’s the company’s recommended queue technology or data store.

But what’s the implication for ongoing support of your services when you end up with multiple CDNs, data stores, queuing technologies, issue-tracking systems, communication tools, build and deployment tools, and languages? It’s all fine when a big team is working on the new shiny thing, but what happens when they leave and you have five people supporting all the “legacy” stuff?

Relatedly, how can the technology leadership make sure program teams still pay attention to department goals that may not match their short-term incentives? You want to save costs on AWS; they want to get stuff out there and optimise VM size later.

At the Financial Times, teams are pretty empowered to make the right decisions for themselves, but this means they’re very resistant to top-down diktats. As a result, company leadership has to find other ways to influence people to do the right thing.

Luckily there’s a fair amount of information out there on how to influence people rather than force them to do things, particularly in the realm of government.

In this article, I’m going to describe what Nudge Theory is, and talk about why I think it is relevant for software development.

What is nudge theory?

“a ‘nudge’ is essentially a means of encouraging or guiding behaviour” – David Halpern, Inside the Nudge unit

Nudges try to influence you rather than force you: putting healthy food on display at eye level, rather than banning sales of junk food; or making sure there are litter bins available and signs explaining that most people throw litter in bins, rather than imposing fines on the spot.

Nudge theory was named and popularised in a book by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. It’s proven attractive to governments, because it’s about small changes, avoiding legislation (which is costly) or financial incentives (again, costly).

Schiphol airport urinals

The canonical example is in Schiphol airport.

The black fleck in the picture is a painting of a fly. It turns out that men like to aim at something, and the fly is in the best place to avoid splashback. This simple change has reduced the cleaning costs by 20%.

UK Organ Donation Register

Another example relates to the UK organ donation register. In the UK, this is an opt in register, and although 90% of people support the idea of organ donation, only 30% of people have signed up to the register.

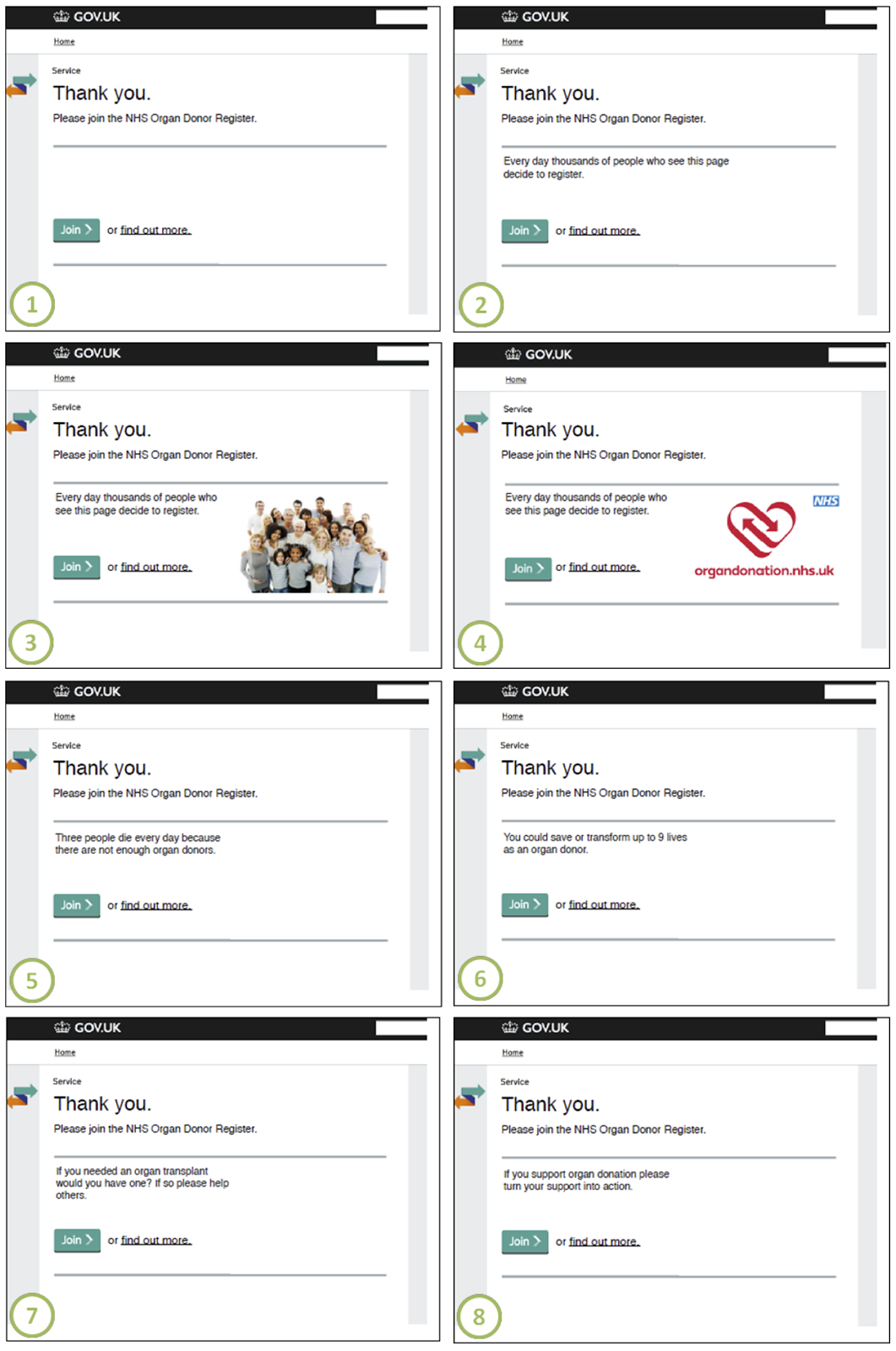

When you renew your car tax online, you’re prompted to sign up. The Nudge Unit ran a randomised controlled trial, with eight alternative versions of the sign-up screen.

Those variants were:

1 – the control

2 – states what other people do in the same situation. There’s evidence that we’re affected by social norms

3 and 4 do the same thing as 2, but with pictures added. Previous research suggested adding relevant pictures increases the chance of someone donating to charity

5 – framed in terms of negative consequences

6 – framed in terms of positive consequences

7 – framed in terms of reciprocity – do to others what you want done to you

8 – pointing out the gap between the 90% that support organ donations vs the 30% that actually register

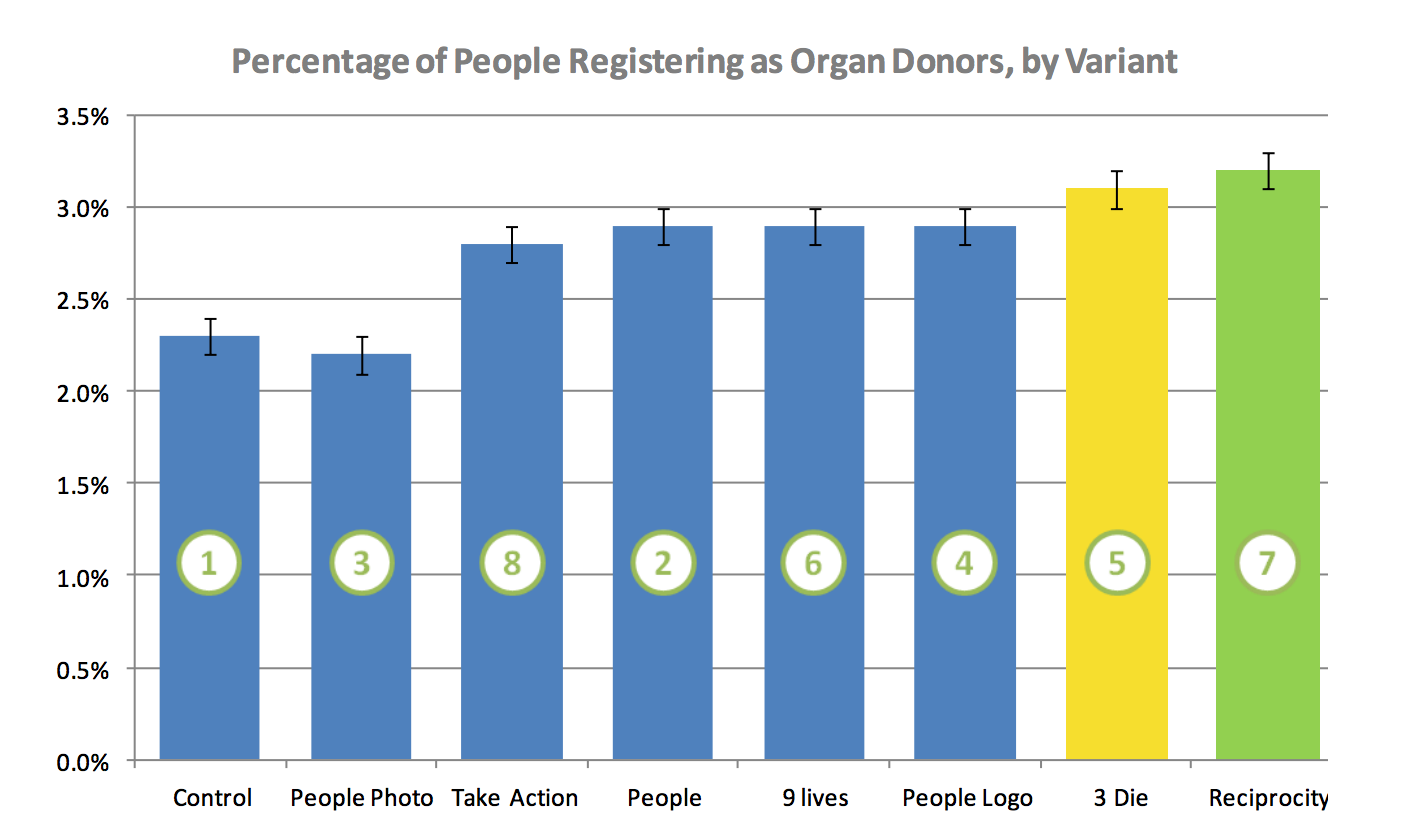

The results were statistically significant:

Reciprocity does the best. Notable is that adding a picture of ‘people’ to the social norms option was WORSE than the control, and framing in terms of negative outcome worked better than framing in terms of positive outcome.

What does this mean in terms of numbers? Well, in a year the difference between control and the best alternative would be around 96,000 extra registrations. Given there are about 21.8 million people registered in total, that’s about a 0.4% increase in the total number of organ donors for the sake of a few changes to a web page.

How can we apply this to software development?

The Nudge Unit came up with an acronym, EAST. They suggest that effective nudges are:

- Easy

- Attractive

- Social

- Timely

I think we can use each of these aspects to more effectively influence teams to do the things we care about as a company.

Easy

If you want someone to do something, you should make it easy: both to understand what the benefit is and to take the appropriate action.

Clear, simple messages, and a good choice of defaults go a long way. We have a strong tendency to stick with the default, which is why it matters whether something is opt in or opt out.

Things we can do to make stuff easy:

- Supply checklists, APIs, example code, libraries.

- Allow people to try your stuff out without having to wait for someone to allocate a key or set up a user account.

- Be customer-focused: make sure people know who to contact. Anytime I see a tumbleweed icon in a team’s slack channel, I wince.

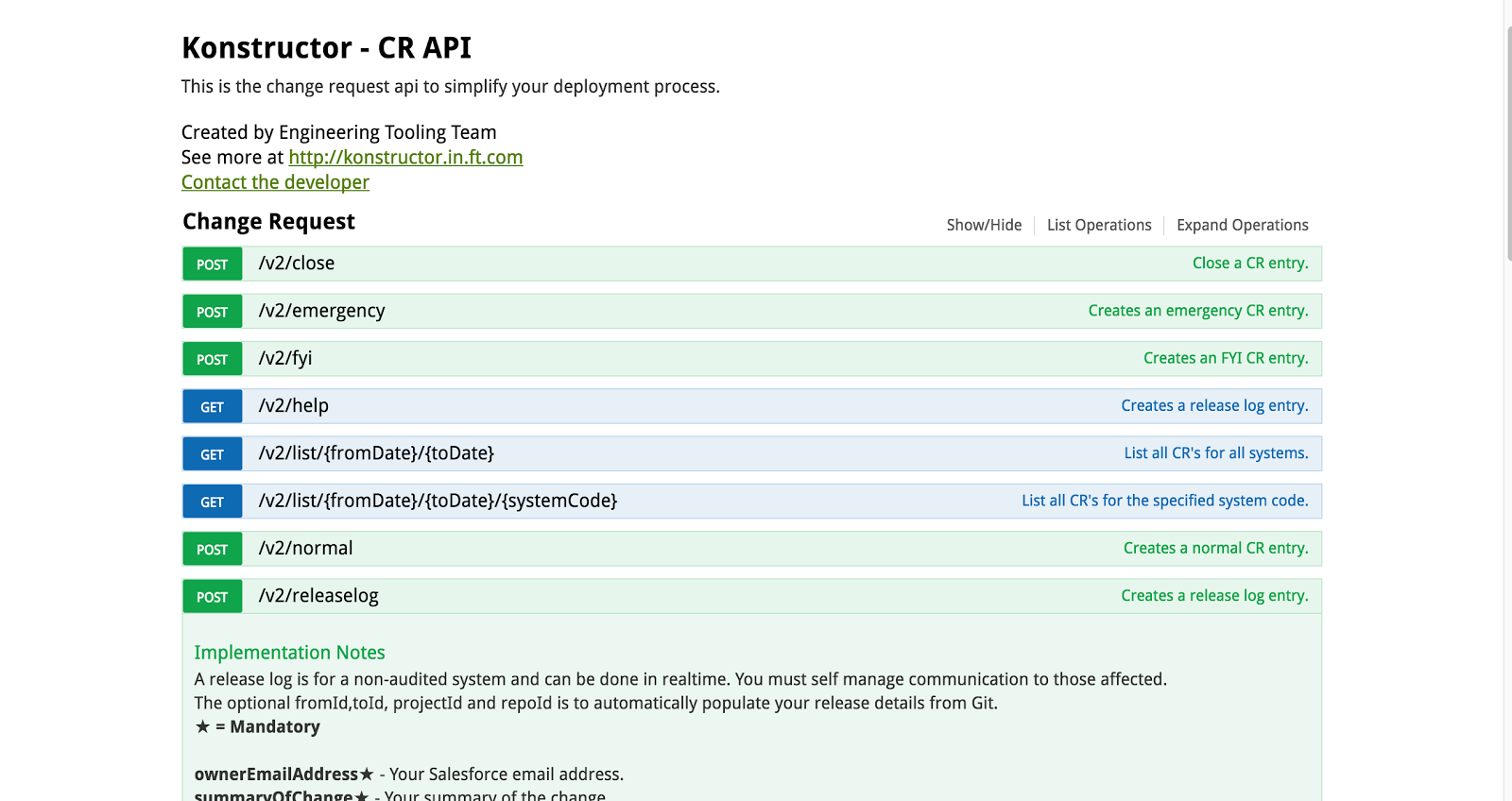

At the FT, we have APIs for creating change requests, which have replaced Salesforce forms.

However, the team have made things even easier by also supplying shell scripts and github webhooks. I integrated the change requests for our systems in minutes thanks to this.

We use the power of defaults with our AWS instances, which default in our staging environments to being shut down overnight and at weekends. Teams have to actively choose to keep them running outside normal working hours rather than actively choosing to turn them off.

Attractive

There are two senses in which you need to make something attractive: firstly, you need to attract people’s attention so they know what you are asking them to do. Then secondly, you need to make that thing attractive by explaining why they should want to do this.

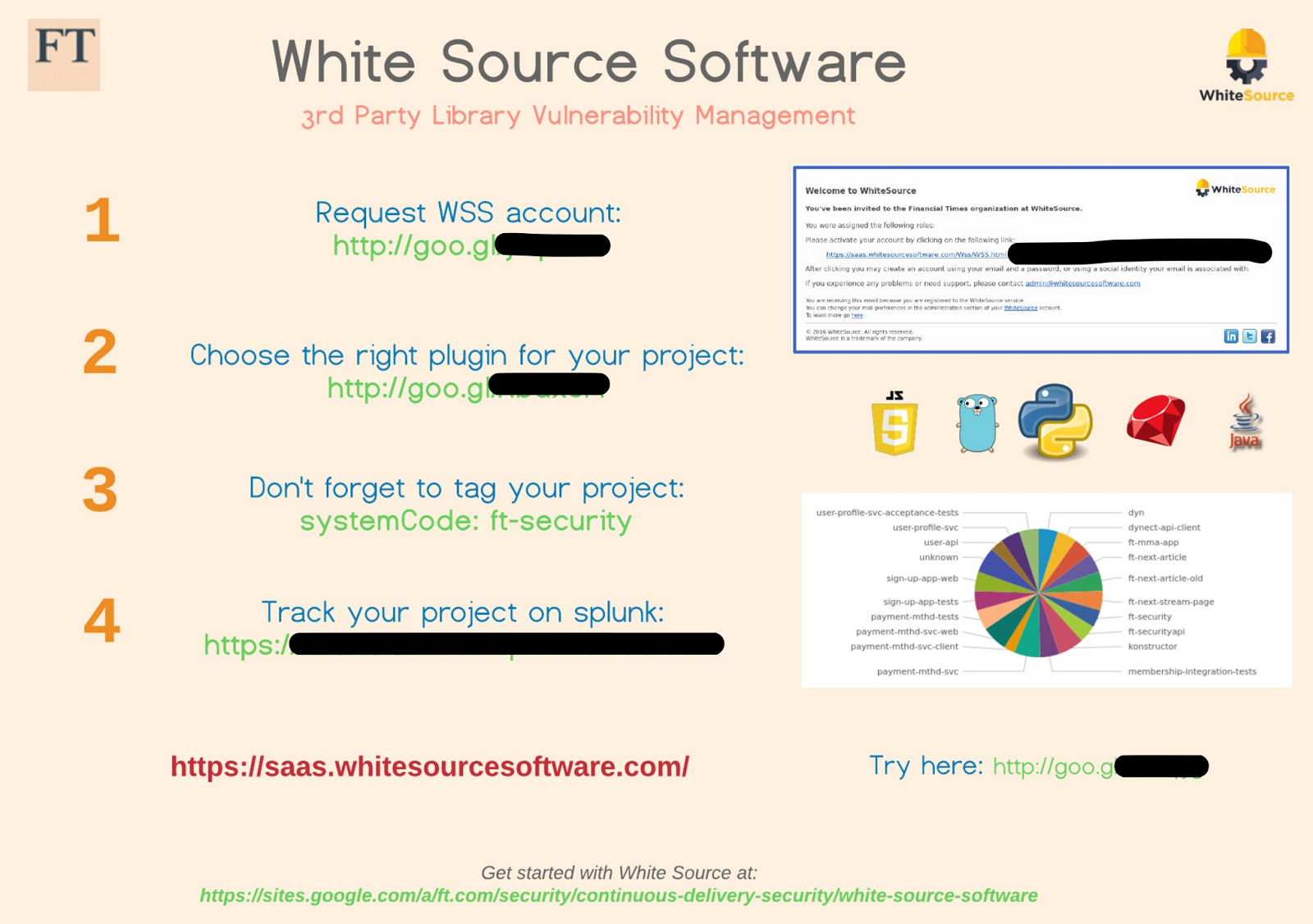

An example at the FT comes from our security team. They want us to use WhiteSource, a tool for scanning libraries in various languages to look for known vulnerabilities.

They’ve documented it comprehensively to explain what it is and why we should use it. They also have a one pager for getting started that tells you exactly what you need to do, and also shows the languages that can use this: I’d assumed there wouldn’t yet be support for Go, but I quickly realised from this one pager that my assumption was wrong.

Social

Humans are social animals. We’re influenced by what other people do: sending someone a letter telling them 95% of people pay their tax on time is proven to make it more likely that they do that too.

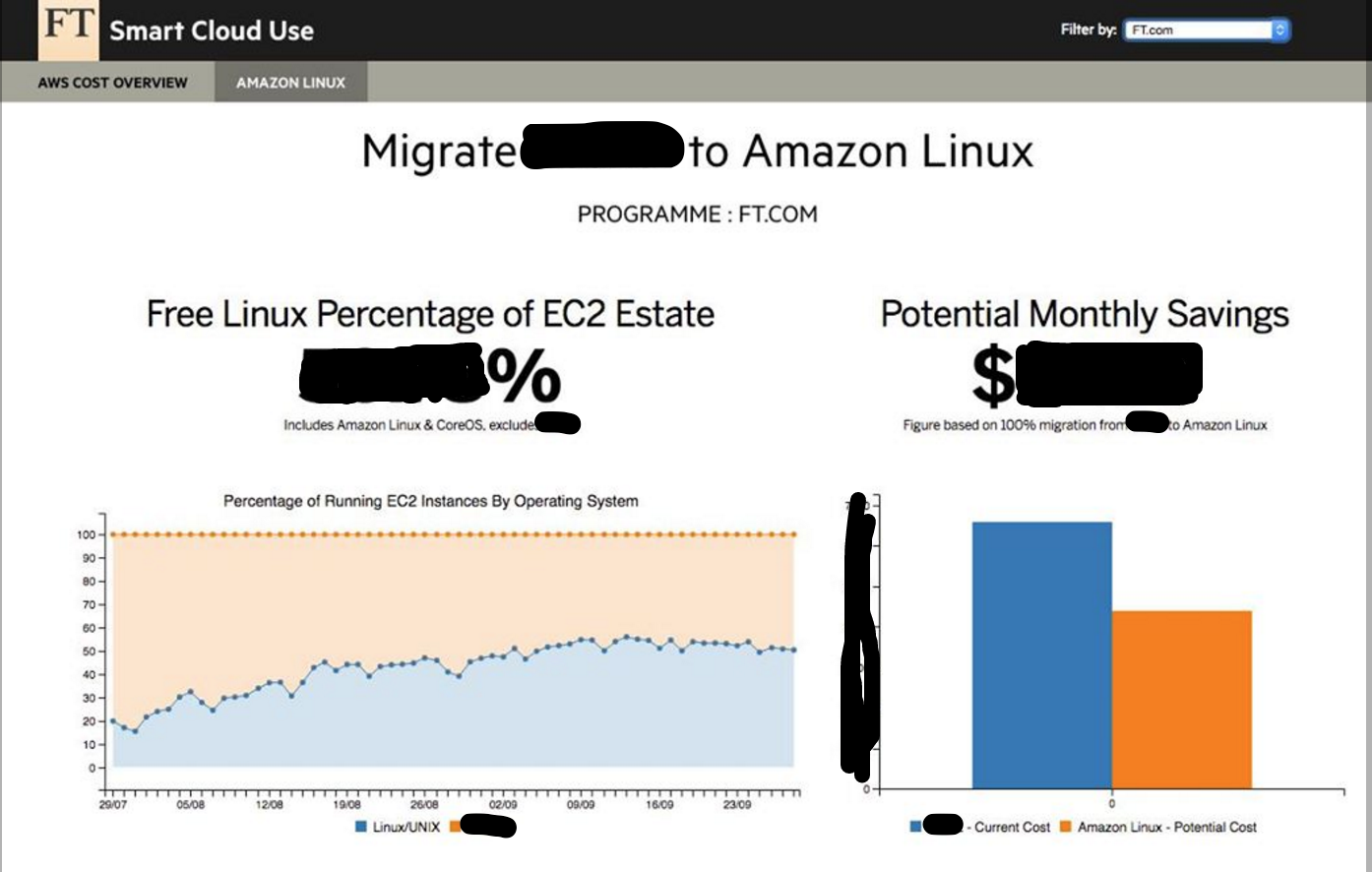

In software development, we can show how other people are doing: for example, wherever possible we want our teams at the FT to migrate to Amazon Linux, because it saves us money – and we have a website that shows each team how much they would save:

We also encourage people to talk about things that have worked for them, in lightning talks or blog posts. When we share information we can show how easy it is to do something and show what people can gain from it. My team adopted Graphite and Grafana because of a really good lightning talk that showed how useful it would be and how easy it would be to integrate it with our systems.

Timely

It’s important to pick the right time to ask people to do things. Usually, that’s when they are just starting to think about how they are going to approach their problem.

If you can provide a solution that already provides most of what the team wants, people are very likely to opt for that.

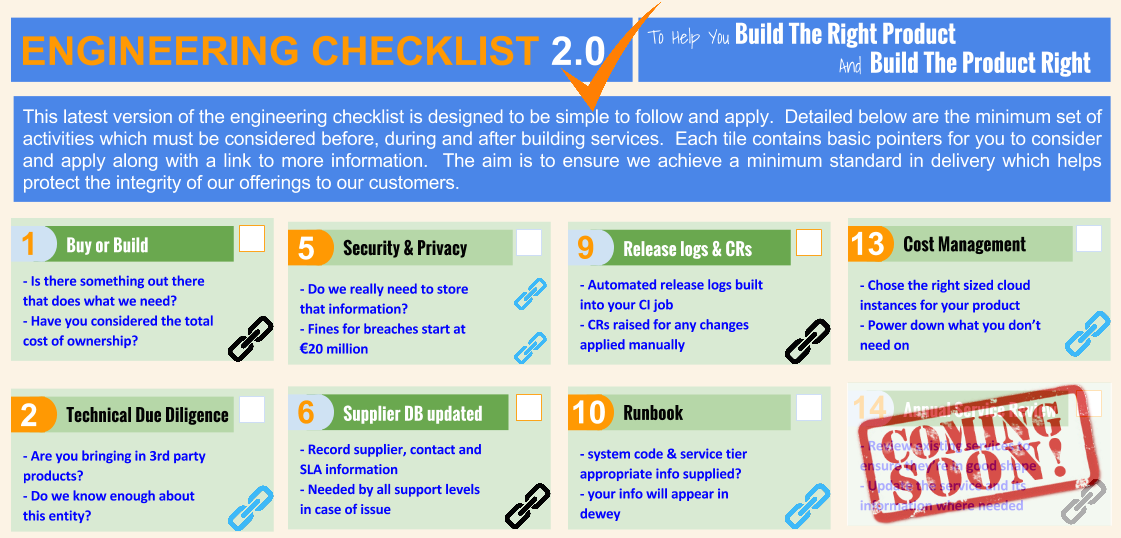

We have an Engineering checklist at the FT that covers the things we expect teams to do.

Here’s part of it:

For each item on the checklist, we link to documentation, libraries, code examples etc. When teams need to get something done, they’re given all the relevant information right then and there.

Having a checklist also makes it easy to do the right thing, and applies some social pressure on teams to do what the other teams are also doing, so it works across several of the levers.

Conclusion

My colleague Matt Chadburn has a great blog post about how a free market economy can be a great thing within a company: let teams pick the best tools, either internal or external. This encourages internal teams to behave like service providers: they need to build great tools, easy to use, well documented, fit for purpose.

Internal teams don’t have a captive market: but they should have a massive advantage. They have their customers right there, and they only need to build tools for a single specific situation.

I think our tooling teams now understand this. They changed the way they worked. They started creating small individual tools and APIs. This means as a client, I can pick and choose. It’s a bit like the unix philosophy in that it favours composability over monolithic design. We now have a set of tools that each do one thing, and do it well. The teams can then compose those however they wish.

But how can an internal team persuade other teams to pick their tools rather than going externally? By making sure those teams know how easy it is to use the tools, the benefits they can get from them, that other people are using them successfully, and making sure they get this information at a time that’s relevant to them. This means nudge theory and EAST can help.